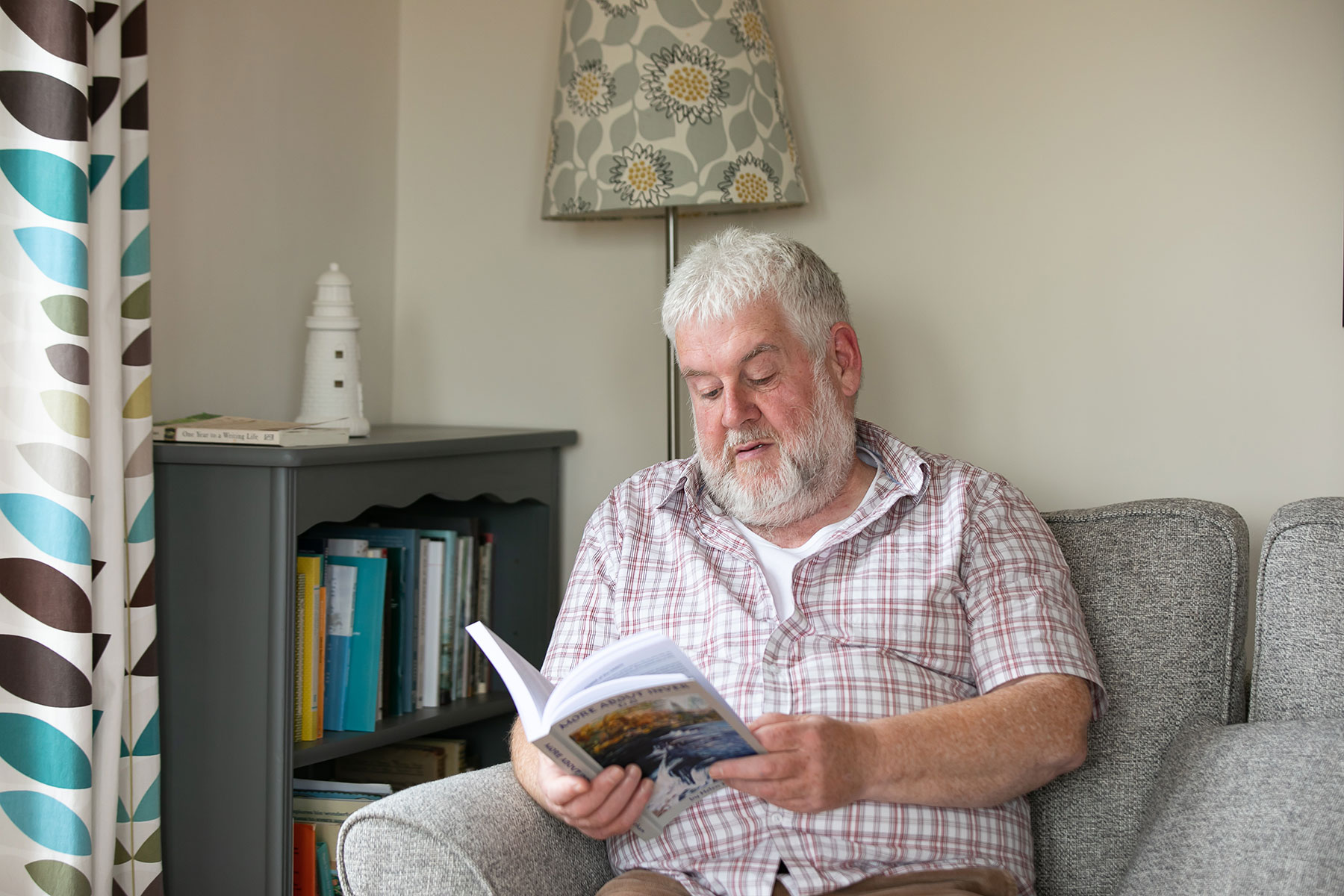

Seven years ago I underwent heart surgery in Dublin. I was about nine hours on the table and thankfully came out the other side. During a visit by my wife, Winifred towards the end of my planned stay in the hospital all I could say in response to her questions was: ‘I don’t know’. She knew I was having difficulty finding words, and it turned out I had had a serious stroke.

I couldn’t speak at first. I had episodes of short-term memory loss and some cognitive problems, but as I had no other physical issues it was hard for people to recognise what was wrong. Winifred got me help. I was very fortunate because she’s a Speech and Language Therapist. She understood what was going on. I’m forever grateful to my wife and family and need to thank them for what they’ve done for me. I didn’t get through this myself – it was because of them.

I don’t recall much in the days immediately after the stroke. I know I was in hospital for a couple of weeks and got great help with speech therapy, physio, and occupational therapy (OT). I got the support I needed, and I was lucky that the stroke team were quite optimistic about the eventual outcome. They arranged for me to see the HSE Community Neurological Rehabilitation (CNR) team when I got home to Donegal, as I had had the stroke on top of major heart surgery. Much of the first year was difficult and I needed that help.